The majority of your work is done in India. You’re in Germany. How exactly does that work?

(Laughs) I think I spent more time in India last year than I did in Germany. Nonetheless, I see my life as being based in Berlin. But as a general rule, it works like this: wherever I need to be, that’s where I am. And Darshan is there in India and we talk with each other every day. He’s more intimate with the technology and the substance of the project, and he has a good working knowledge of everything related to the Internet of Things. I, on the other hand, organize the business and sales aspects — and for the most part, I can do that very well from Berlin.

Which challenges are you facing during the pilot phase?

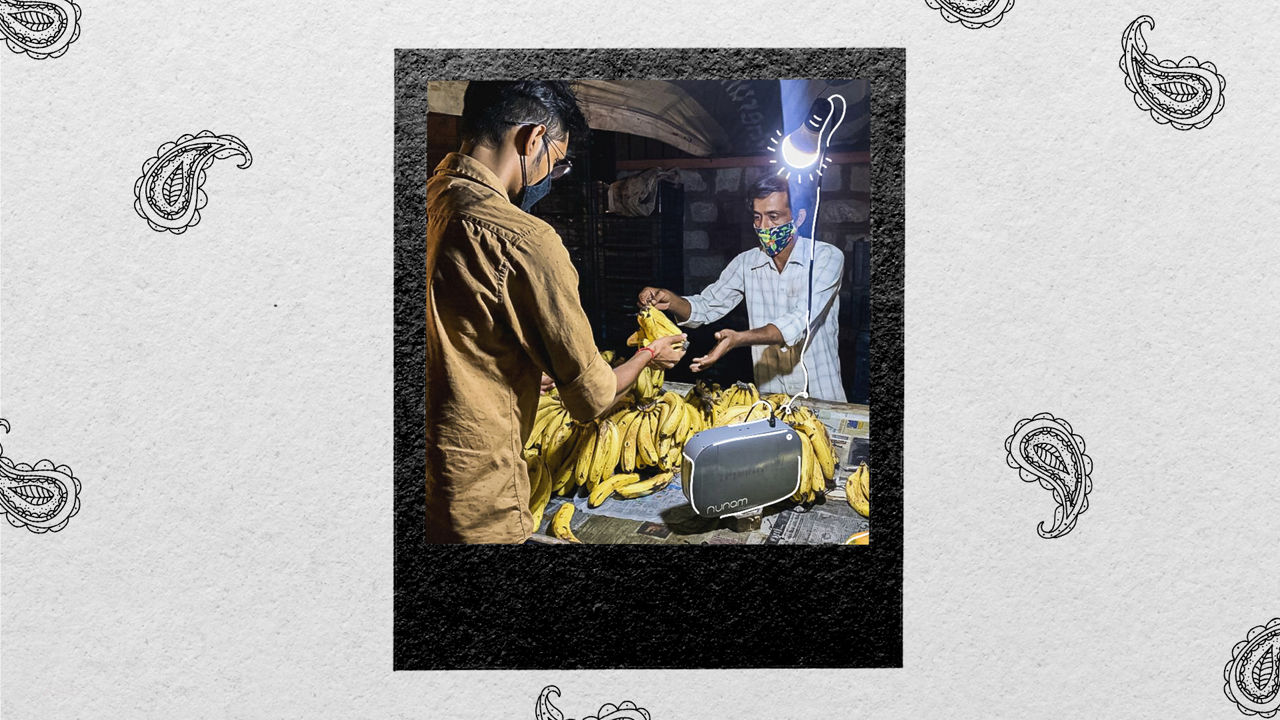

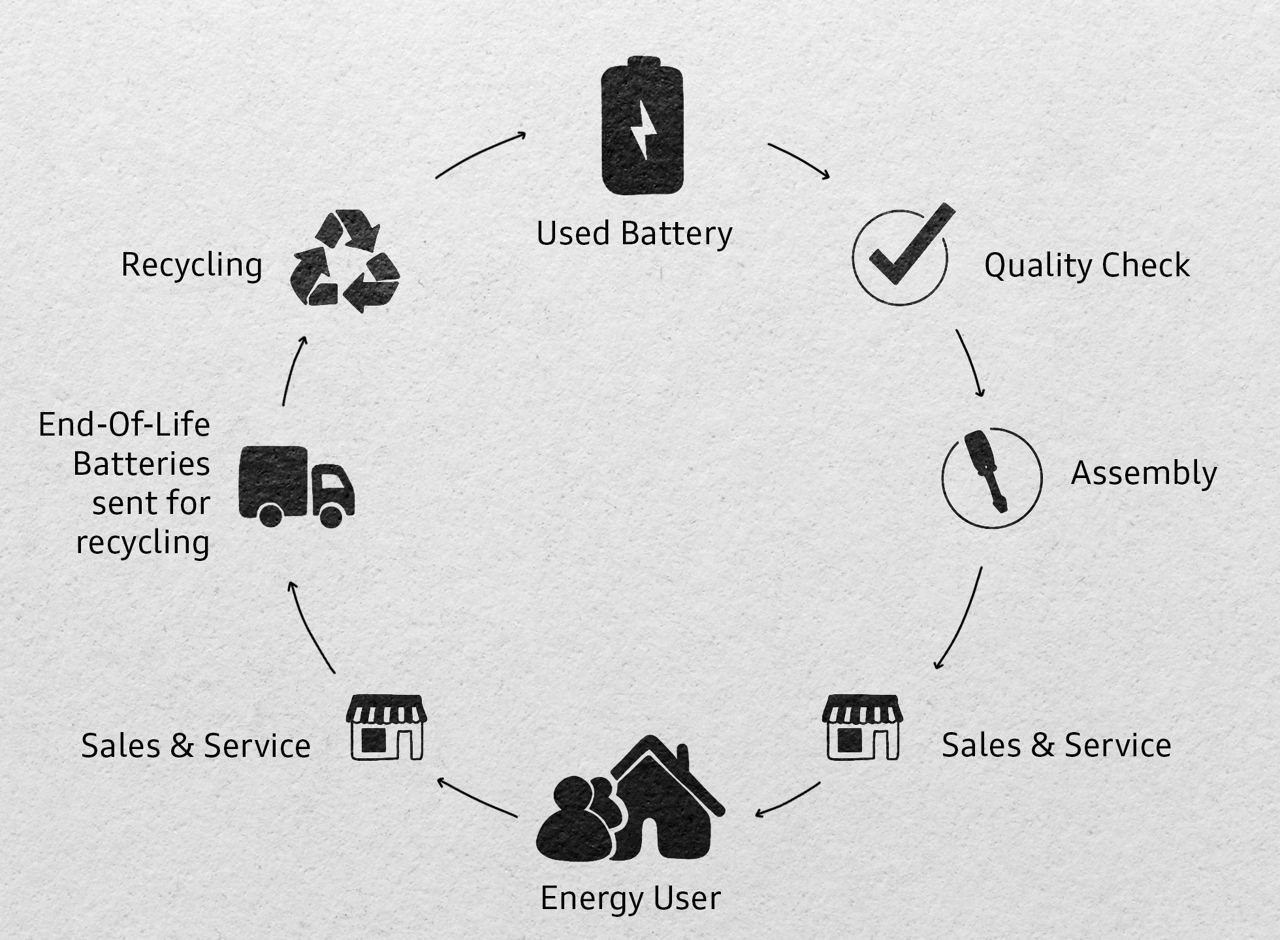

On the one hand, our project and our product needs to become well-known. It’s important that we win our users’ trust. In the case of new projects, it can often take a while before that happens. (Smiles.) On the other hand, we need to consider distribution channels: should we sell to electronics retailers, directly to customers, or exclusively online? It’s important to us that we can sell the renewable energy storage unit as inexpensively as possible so that even the poorest customers can have access to a bit of electricity. It’s also important that we can be sure of getting the units back. Overall, there are a number of exciting challenges facing us this year.

What are your plans for the year 2020?

We are focusing on our pilot project and gathering experience and data. Our goal is to develop around 25 prototypes from laptop batteries and then distribute them to customers in rural areas.

The results and our analytics data about the battery cell usage will then be shared with researchers and anyone who is interested. We are already cooperating with the TU Berlin in this regard. The goal of our startup, most of all, is to motivate other teams and organizations to start similar projects. The energy is there, we just need to use it.

Thank you very much for the interview, Prodip, and we wish you all the best!

.jpg)